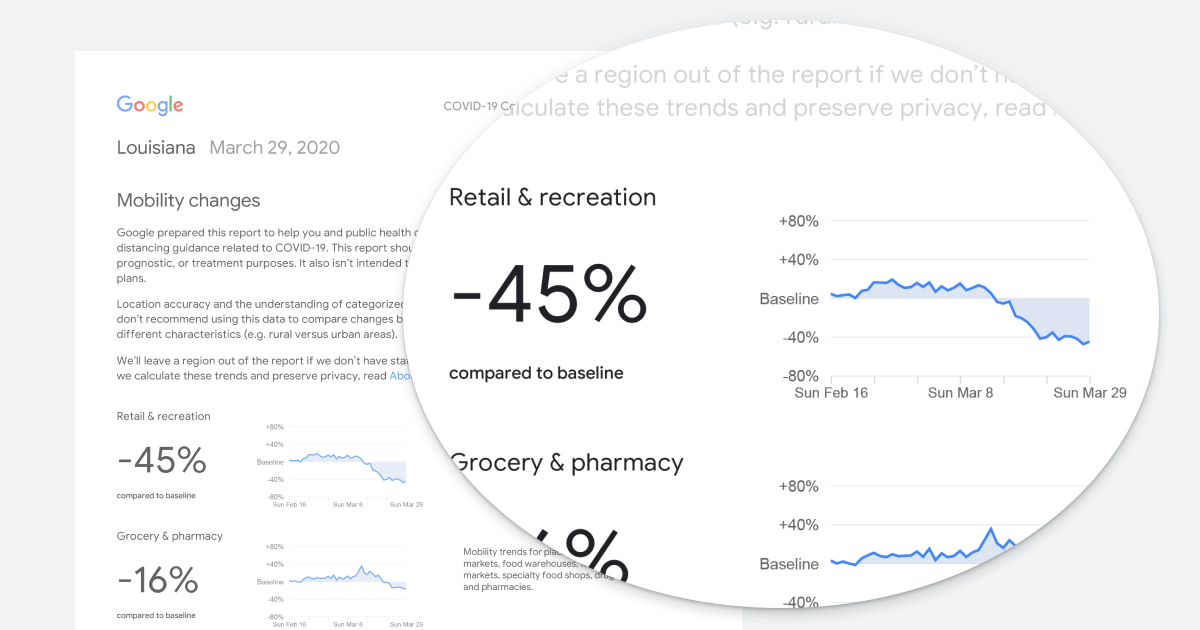

No kappas! Näyttää ihan oikeasti siltä, että rapsa on vedetty pois julkisesti saatavilta. Onneksi olin kaivanut sen oleellisen jo siihen viestiin.

PDF:ää en valitettavasti ladannut vaan esikatselin sitä web-vieverillä.

Google-haun välimuisti kuitenkin vielä antaa tekstisisältöä (ilman graafeja yms.)

webcache PDF-dokkari tekstimuodossa

Tämä on html-versio tiedostosta https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/sph/ide/gida-fellowships/Imperial-College-COVID19-Europe-estimates-and-NPI-impact-30-03-2020.pdf. Google muuntaa indeksoidut sivut automaattisesti html-muotoon.

Vinkki: löydät hakutermisi sivulta nopeasti painamalla Ctrl+F tai ⌘-F (Mac) ja käyttämällä näkyviin tulevaa hakupalkkia.

Page 1

30 March 2020

Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team

DOI: Spiral: Report 13: Estimating the number of infections and the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in 11 European countries

Page 1 of 35

Estimating the number of infections and the impact of non-

pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in 11 European countries

Seth Flaxman*, Swapnil Mishra*, Axel Gandy*, H Juliette T Unwin, Helen Coupland, Thomas A Mellan, Harrison

Zhu, Tresnia Berah, Jeffrey W Eaton, Pablo N P Guzman, Nora Schmit, Lucia Cilloni, Kylie E C Ainslie, Marc

Baguelin, Isobel Blake, Adhiratha Boonyasiri, Olivia Boyd, Lorenzo Cattarino, Constanze Ciavarella, Laura Cooper,

Zulma Cucunubá, Gina Cuomo-Dannenburg, Amy Dighe, Bimandra Djaafara, Ilaria Dorigatti, Sabine van Elsland,

Rich FitzJohn, Han Fu, Katy Gaythorpe, Lily Geidelberg, Nicholas Grassly, Will Green, Timothy Hallett, Arran

Hamlet, Wes Hinsley, Ben Jeffrey, David Jorgensen, Edward Knock, Daniel Laydon, Gemma Nedjati-Gilani, Pierre

Nouvellet, Kris Parag, Igor Siveroni, Hayley Thompson, Robert Verity, Erik Volz, Caroline Walters, Haowei Wang,

Yuanrong Wang, Oliver Watson, Peter Winskill, Xiaoyue Xi, Charles Whittaker, Patrick GT Walker, Azra Ghani,

Christl A. Donnelly, Steven Riley, Lucy C Okell, Michaela A C Vollmer, Neil M. Ferguson1 and Samir Bhatt*1

Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, Imperial College London

Department of Mathematics, Imperial College London

WHO Collaborating Centre for Infectious Disease Modelling

MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis

Abdul Latif Jameel Institute for Disease and Emergency Analytics, Imperial College London

Department of Statistics, University of Oxford

*Contributed equally 1Correspondence: neil.ferguson@imperial.ac.uk, s.bhatt@imperial.ac.uk

Summary

Following the emergence of a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) and its spread outside of China, Europe

is now experiencing large epidemics. In response, many European countries have implemented

unprecedented non-pharmaceutical interventions including case isolation, the closure of schools and

universities, banning of mass gatherings and/or public events, and most recently, widescale social

distancing including local and national lockdowns.

In this report, we use a semi-mechanistic Bayesian hierarchical model to attempt to infer the impact

of these interventions across 11 European countries. Our methods assume that changes in the

reproductive number – a measure of transmission - are an immediate response to these interventions

being implemented rather than broader gradual changes in behaviour. Our model estimates these

changes by calculating backwards from the deaths observed over time to estimate transmission that

occurred several weeks prior, allowing for the time lag between infection and death.

One of the key assumptions of the model is that each intervention has the same effect on the

reproduction number across countries and over time. This allows us to leverage a greater amount of

data across Europe to estimate these effects. It also means that our results are driven strongly by the

data from countries with more advanced epidemics, and earlier interventions, such as Italy and Spain.

We find that the slowing growth in daily reported deaths in Italy is consistent with a significant impact

of interventions implemented several weeks earlier. In Italy, we estimate that the effective

reproduction number, Rt , dropped to close to 1 around the time of lockdown (11th March), although

with a high level of uncertainty.

Overall, we estimate that countries have managed to reduce their reproduction number. Our

estimates have wide credible intervals and contain 1 for countries that have implemented all

interventions considered in our analysis. This means that the reproduction number may be above or

below this value. With current interventions remaining in place to at least the end of March, we

estimate that interventions across all 11 countries will have averted 59,000 deaths up to 31 March

[95% credible interval 21,000-120,000]. Many more deaths will be averted through ensuring that

interventions remain in place until transmission drops to low levels. We estimate that, across all 11

countries between 7 and 43 million individuals have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 up to 28th March,

representing between 1.88% and 11.43% of the population. The proportion of the population infected

Page 2

30 March 2020

Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team

DOI: Spiral: Report 13: Estimating the number of infections and the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in 11 European countries

Page 2 of 35

to date – the attack rate - is estimated to be highest in Spain followed by Italy and lowest in Germany

and Norway, reflecting the relative stages of the epidemics.

Given the lag of 2-3 weeks between when transmission changes occur and when their impact can be

observed in trends in mortality, for most of the countries considered here it remains too early to be

certain that recent interventions have been effective. If interventions in countries at earlier stages of

their epidemic, such as Germany or the UK, are more or less effective than they were in the countries

with advanced epidemics, on which our estimates are largely based, or if interventions have improved

or worsened over time, then our estimates of the reproduction number and deaths averted would

change accordingly. It is therefore critical that the current interventions remain in place and trends in

cases and deaths are closely monitored in the coming days and weeks to provide reassurance that

transmission of SARS-Cov-2 is slowing.

SUGGESTED CITATION

Seth Flaxman, Swapnil Mishra, Axel Gandy et al . Estimating the number of infections and the impact of non-

pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in 11 European countries. Imperial College London (2020), doi:

Spiral: Report 13: Estimating the number of infections and the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in 11 European countries

Page 3

30 March 2020

Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team

DOI: Spiral: Report 13: Estimating the number of infections and the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in 11 European countries

Page 3 of 35

1 Introduction

Following the emergence of a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in Wuhan, China in December 2019 and

its global spread, large epidemics of the disease, caused by the virus designated COVID-19, have

emerged in Europe. In response to the rising numbers of cases and deaths, and to maintain the

capacity of health systems to treat as many severe cases as possible, European countries, like those in

other continents, have implemented or are in the process of implementing measures to control their

epidemics. These large-scale non-pharmaceutical interventions vary between countries but include

social distancing (such as banning large gatherings and advising individuals not to socialize outside

their households), border closures, school closures, measures to isolate symptomatic individuals and

their contacts, and large-scale lockdowns of populations with all but essential internal travel banned.

Understanding firstly, whether these interventions are having the desired impact of controlling the

epidemic and secondly, which interventions are necessary to maintain control, is critical given their

large economic and social costs.

The key aim of these interventions is to reduce the effective reproduction number, , of the infection,

a fundamental epidemiological quantity representing the average number of infections, at time t, per

infected case over the course of their infection. If is maintained at less than 1, the incidence of new

infections decreases, ultimately resulting in control of the epidemic. If is greater than 1, then

infections will increase (dependent on how much greater than 1 the reproduction number is) until the

epidemic peaks and eventually declines due to acquisition of herd immunity.

In China, strict movement restrictions and other measures including case isolation and quarantine

began to be introduced from 23rd January, which achieved a downward trend in the number of

confirmed new cases during February, resulting in zero new confirmed indigenous cases in Wuhan by

March 19th. Studies have estimated how changed during this time in different areas of China from

around 2-4 during the uncontrolled epidemic down to below 1, with an estimated 7-9 fold decrease

in the number of daily contacts per person.1,2 Control measures such as social distancing, intensive

testing, and contact tracing in other countries such as Singapore and South Korea have successfully

reduced case incidence in recent weeks, although there is a risk the virus will spread again once control

measures are relaxed.3,4

The epidemic began slightly later in Europe, from January or later in different regions.5 Countries have

implemented different combinations of control measures and the level of adherence to government

recommendations on social distancing is likely to vary between countries, in part due to different

levels of enforcement.

Estimating reproduction numbers for SARS-CoV-2 presents challenges due to the high proportion of

infections not detected by health systems1,6,7 and regular changes in testing policies, resulting in

different proportions of infections being detected over time and between countries. Most countries

so far only have the capacity to test a small proportion of suspected cases and tests are reserved for

severely ill patients or for high-risk groups (e.g. contacts of cases). Looking at case data, therefore,

gives a systematically biased view of trends.

An alternative way to estimate the course of the epidemic is to back-calculate infections from

observed deaths. Reported deaths are likely to be more reliable, although the early focus of most

surveillance systems on cases with reported travel histories to China may mean that some early deaths

will have been missed. Whilst the recent trends in deaths will therefore be informative, there is a time

lag in observing the effect of interventions on deaths since there is a 2-3-week period between

infection, onset of symptoms and outcome.

Page 4

30 March 2020

Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team

DOI: Spiral: Report 13: Estimating the number of infections and the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in 11 European countries

Page 4 of 35

In this report, we fit a novel Bayesian mechanistic model of the infection cycle to observed deaths in

11 European countries, inferring plausible upper and lower bounds (Bayesian credible intervals) of the

total populations infected (attack rates), case detection probabilities, and the reproduction number

over time ( Rt ). We fit the model jointly to COVID-19 data from all these countries to assess whether

there is evidence that interventions have so far been successful at reducing Rt below 1, with the strong

assumption that particular interventions are achieving a similar impact in different countries and that

the efficacy of those interventions remains constant over time. The model is informed more strongly

by countries with larger numbers of deaths and which implemented interventions earlier, therefore

estimates of recent Rt in countries with more recent interventions are contingent on similar

intervention impacts. Data in the coming weeks will enable estimation of country-specific Rt with

greater precision.

Model and data details are presented in the appendix, validation and sensitivity are also presented in

the appendix, and general limitations presented below in the conclusions.

2 Results

The timing of interventions should be taken in the context of when an individual country’s epidemic

started to grow along with the speed with which control measures were implemented. Italy was the

first to begin intervention measures, and other countries followed soon afterwards (Figure 1). Most

interventions began around 12th-14th March. We analyzed data on deaths up to 28th March, giving a

2-3-week window over which to estimate the effect of interventions. Currently, most countries in our

study have implemented all major non-pharmaceutical interventions.

For each country, we model the number of infections, the number of deaths, and , the effective

reproduction number over time, with changing only when an intervention is introduced (Figure 2-

12). is the average number of secondary infections per infected individual, assuming that the

interventions that are in place at time t stay in place throughout their entire infectious period. Every

country has its own individual starting reproduction number before interventions take place.

Specific interventions are assumed to have the same relative impact on in each country when they

were introduced there and are informed by mortality data across all countries.

Page 5

30 March 2020

Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team

DOI: Spiral: Report 13: Estimating the number of infections and the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in 11 European countries

Page 5 of 35

Figure 1: Intervention timings for the 11 European countries included in the analysis. For further

details see Appendix 8.6.

2.1 Estimated true numbers of infections and current attack rates

In all countries, we estimate there are orders of magnitude fewer infections detected (Figure 2) than

true infections, mostly likely due to mild and asymptomatic infections as well as limited testing

capacity. In Italy, our results suggest that, cumulatively, 5.9 [1.9-15.2] million people have been

infected as of March 28th, giving an attack rate of 9.8% [3.2%-25%] of the population (Table 1). Spain

has recently seen a large increase in the number of deaths, and given its smaller population, our model

estimates that a higher proportion of the population, 15.0% (7.0 [1.8-19] million people) have been

infected to date. Germany is estimated to have one of the lowest attack rates at 0.7% with 600,000

[240,000-1,500,000] people infected.

Page 6

30 March 2020

Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team

DOI: Spiral: Report 13: Estimating the number of infections and the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in 11 European countries

Page 6 of 35

Table 1: Posterior model estimates of percentage of total population infected as of 28th March 2020.

2.2 Reproduction numbers and impact of interventions

Averaged across all countries, we estimate initial reproduction numbers of around 3.87 [3.01-4.66],

which is in line with other estimates.1,8 These estimates are informed by our choice of serial interval

distribution and the initial growth rate of observed deaths. A shorter assumed serial interval results in

lower starting reproduction numbers (Appendix 8.4.2, Appendix 8.4.6). The initial reproduction

numbers are also uncertain due to (a) importation being the dominant source of new infections early

in the epidemic, rather than local transmission (b) possible under-ascertainment in deaths particularly

before testing became widespread.

We estimate large changes in in response to the combined non-pharmaceutical interventions. Our

results, which are driven largely by countries with advanced epidemics and larger numbers of deaths

(e.g. Italy, Spain), suggest that these interventions have together had a substantial impact on

transmission, as measured by changes in the estimated reproduction number Rt . Across all countries

we find current estimates of Rt to range from a posterior mean of 0.97 [0.14-2.14] for Norway to a

posterior mean of 2.64 [1.40-4.18] for Sweden, with an average of 1.43 across the 11 country posterior

means, a 64% reduction compared to the pre-intervention values. We note that these estimates are

contingent on intervention impact being the same in different countries and at different times. In all

countries but Sweden, under the same assumptions, we estimate that the current reproduction

number includes 1 in the uncertainty range. The estimated reproduction number for Sweden is higher,

not because the mortality trends are significantly different from any other country, but as an artefact

of our model, which assumes a smaller reduction in Rt because no full lockdown has been ordered so

far. Overall, we cannot yet conclude whether current interventions are sufficient to drive below 1

(posterior probability of being less than 1.0 is 44% on average across the countries). We are also

unable to conclude whether interventions may be different between countries or over time.

There remains a high level of uncertainty in these estimates. It is too early to detect substantial

intervention impact in many countries at earlier stages of their epidemic (e.g. Germany, UK, Norway).

Many interventions have occurred only recently, and their effects have not yet been fully observed

due to the time lag between infection and death. This uncertainty will reduce as more data become

available. For all countries, our model fits observed deaths data well (Bayesian goodness of fit tests).

We also found that our model can reliably forecast daily deaths 3 days into the future, by withholding

the latest 3 days of data and comparing model predictions to observed deaths (Appendix 8.3).

The close spacing of interventions in time made it statistically impossible to determine which had the

greatest effect (Figure 1, Figure 4). However, when doing a sensitivity analysis (Appendix 8.4.3) with

uninformative prior distributions (where interventions can increase deaths) we find similar impact of

Country

% of total population infected (mean [95% credible interval])

Austria

1.1% [0.36%-3.1%]

Belgium

3.7% [1.3%-9.7%]

Denmark

1.1% [0.40%-3.1%]

France

3.0% [1.1%-7.4%]

Germany

0.72% [0.28%-1.8%]

Italy

9.8% [3.2%-26%]

Norway

0.41% [0.09%-1.2%]

Spain

15% [3.7%-41%]

Sweden

3.1% [0.85%-8.4%]

Switzerland

3.2% [1.3%-7.6%]

United Kingdom

2.7% [1.2%-5.4%]

Page 7

30 March 2020

Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team

DOI: Spiral: Report 13: Estimating the number of infections and the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in 11 European countries

Page 7 of 35

interventions, which shows that our choice of prior distribution is not driving the effects we see in the

main analysis.

(A) Austria

(B) Belgium

(C) Denmark

(D) France

0

10000

20000

30000

40000

D

a

ily n

u

m

b

e

r o

f in

fe

c

tio

n

s

0

5

10

15

20

time

d

e

a

th

s

0

2

4

6

R

t

Interventions

Complete lockdown

Public events banned

School closure

Self isolation

Social distancing

50%

95%

0

50000

100000

150000

D

a

ily n

u

m

b

e

r o

f in

fe

c

tio

n

s

0

20

40

60

time

d

e

a

th

s

0

2

4

6

R

t

Interventions

Complete lockdown

Public events banned

School closure

Self isolation

Social distancing

50%

95%

0

5000

10000

15000

20000

25000

D

a

ily n

u

m

b

e

r o

f in

fe

c

tio

n

s

0

5

10

time

d

e

a

th

s

0

2

4

R

t

Interventions

Complete lockdown

Public events banned

School closure

Self isolation

Social distancing

50%

95%

0e+00

2e+05

4e+05

6e+05

D

a

ily n

u

m

b

e

r o

f in

fe

c

tio

n

s

0

100

200

300

400

time

d

e

a

th

s

0

2

4

R

t

Interventions

Complete lockdown

Public events banned

School closure

Self isolation

Social distancing

50%

95%

Page 8

30 March 2020

Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team

DOI: Spiral: Report 13: Estimating the number of infections and the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in 11 European countries

Page 8 of 35

(E) Germany

(F) Italy

(G) Norway

(H) Spain

0

50000

100000

150000

200000

D

a

ily n

u

m

b

e

r o

f in

fe

c

tio

n

s

0

25

50

75

time

d

e

a

th

s

0

2

4

6

R

t

Interventions

Complete lockdown

Public events banned

School closure

Self isolation

Social distancing

50%

95%

0

500000

1000000

1500000

D

a

ily n

u

m

b

e

r o

f in

fe

c

tio

n

s

0

500

1000

1500

time

d

e

a

th

s

0

1

2

3

4

R

t

Interventions

Complete lockdown

Public events banned

School closure

Self isolation

Social distancing

50%

95%

0

2000

4000

6000

D

a

ily n

u

m

b

e

r o

f in

fe

c

tio

n

s

0

1

2

3

4

5

time

d

e

a

th

s

0

2

4

R

t

Interventions

Complete lockdown

Public events banned

School closure

Self isolation

Social distancing

50%

95%

0e+00

1e+06

2e+06

3e+06

D

a

ily n

u

m

b

e

r o

f in

fe

c

tio

n

s

0

300

600

900

time

d

e

a

th

s

0

2

4

6

R

t

Interventions

Complete lockdown

Public events banned

School closure

Self isolation

Social distancing

50%

95%

Page 9

30 March 2020

Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team

DOI: Spiral: Report 13: Estimating the number of infections and the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in 11 European countries

Page 9 of 35

Figure 2: Country-level estimates of infections, deaths and Rt. Left: daily number of infections, brown

bars are reported infections, blue bands are predicted infections, dark blue 50% credible interval (CI),

light blue 95% CI. The number of daily infections estimated by our model drops immediately after an

intervention, as we assume that all infected people become immediately less infectious through the

intervention. Afterwards, if the Rt is above 1, the number of infections will starts growing again.

Middle: daily number of deaths, brown bars are reported deaths, blue bands are predicted deaths, CI

as in left plot. Right: time-varying reproduction number , dark green 50% CI, light green 95% CI.

Icons are interventions shown at the time they occurred.

(I) Sweden

(J) Switzerland

(K) United Kingdom

0

50000

100000

150000

D

a

ily n

u

m

b

e

r o

f in

fe

c

tio

n

s

0

10

20

time

d

e

a

th

s

0

2

4

6

R

t

Interventions

Complete lockdown

Public events banned

School closure

Self isolation

Social distancing

50%

95%

0

25000

50000

75000

D

a

ily n

u

m

b

e

r o

f in

fe

c

tio

n

s

0

20

40

60

time

d

e

a

th

s

0

2

4

R

t

Interventions

Complete lockdown

Public events banned

School closure

Self isolation

Social distancing

50%

95%

0e+00

1e+05

2e+05

3e+05

4e+05

5e+05

D

a

ily n

u

m

b

e

r o

f in

fe

c

tio

n

s

0

50

100

150

200

time

d

e

a

th

s

0

2

4

R

t

Interventions

Complete lockdown

Public events banned

School closure

Self isolation

Social distancing

50%

95%

Page 10

30 March 2020

Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team

DOI: Spiral: Report 13: Estimating the number of infections and the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in 11 European countries

Page 10 of 35

Table 2: Total forecasted deaths since the beginning of the epidemic up to 31 March in our model

and in a counterfactual model (assuming no intervention had taken place). Estimated averted deaths

over this time period as a result of the interventions. Numbers in brackets are 95% credible intervals.

Country

Observed

Deaths to 28th

March

Model estimated

deaths to 28th

March

Model

estimated

deaths to 31

March

Model

estimated

deaths to 31

March

Model deaths

averted to 31

March

(observed)

(our model)

(our model)

(counterfactual

model

assuming no

interventions

have occurred)

(difference

between

counterfactual

and actual)

Austria

68

88 [57 - 130]

140 [88 - 210] 280 [140 -

560]

140 [34 -

380]

Belgium

289

310 [230 - 420] 510 [370 -

730]

1,100 [590 -

2,100]

560 [160 -

1,500]

Denmark

52

61 [38 - 92]

93 [58 - 140] 160 [84 - 310] 69 [15 - 200]

France

1,995

1,900 [1,500 -

2,500]

3,100 [2,300 -

4,200]

5,600 [3,600 -

8,500]

2,500 [1,000

Germany

325

320 [240 - 410] 570 [400 -

810]

1,100 [570 -

2,400]

550 [91 -

1,800]

Italy

9,136

10,000 [8,200 -

13,000]

14,000

[11,000 -

19,000]

52,000

[27,000 -

98,000]

38,000

[13,000 -

84,000]

Norway

16

17 [7 - 33]

26 [11 - 51]

36 [14 - 81]

9.9 [0.82 -

38]

Spain

4,858

4,700 [3,700 -

6,100]

7,700 [5,500 -

11,000]

24,000

[13,000 -

44,000]

16,000

[5,400 -

35,000]

Sweden

92

89 [61 - 120]

160 [110 -

240]

240 [140 -

440]

82 [12 - 250]

Switzerland

197

190 [140 - 250] 310 [220 -

440]

650 [330 -

1,500]

340 [71 -

1,100]

United

Kingdom

759

810 [610 -

1,100]

1,500 [1,000 -

2,100]

1,800 [1,200 -

2,900]

370 [73 -

1,000]

All

17,787

19,000 [16,000 -

22,000]

28,000

[23,000 -

36,000]

87,000

[53,000 -

140,000]

59,000

[21,000 -

120,000]

Page 11

30 March 2020

Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team

DOI: Spiral: Report 13: Estimating the number of infections and the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in 11 European countries

Page 11 of 35

2.3 Estimated impact of interventions on deaths

Table 2 shows total forecasted deaths since the beginning of the epidemic up to and including 31

March under our fitted model and under the counterfactual model, which predicts what would have

happened if no interventions were implemented (and = 0 i.e. the initial reproduction number

estimated before interventions). Again, the assumption in these predictions is that intervention

impact is the same across countries and time. The model without interventions was unable to capture

recent trends in deaths in several countries, where the rate of increase had clearly slowed (Figure 3).

Trends were confirmed statistically by Bayesian leave-one-out cross-validation and the widely

applicable information criterion assessments – WAIC).

By comparing the deaths predicted under the model with no interventions to the deaths predicted in

our intervention model, we calculated the total deaths averted up to the end of March. We find that,

across 11 countries, since the beginning of the epidemic, 59,000 [21,000-120,000] deaths have been

averted due to interventions. In Italy and Spain, where the epidemic is advanced, 38,000 [13,000-

84,000] and 16,000 [5,400-35,000] deaths have been averted, respectively. Even in the UK, which is

much earlier in its epidemic, we predict 370 [73-1,000] deaths have been averted.

These numbers give only the deaths averted that would have occurred up to 31 March. If we were to

include the deaths of currently infected individuals in both models, which might happen after 31

March, then the deaths averted would be substantially higher.

(a) Italy

(b) Spain

![]()

![]()

![]()