En osaa yhtään ennustaa missä määrin 2020-luvussa tulee olemaan yhtäläisyyksiä ja eroavaisuuksia vs. 70-luku. Eli 70-luvun tutkiminen voi olla hyödyllistä tai sitten ei.

Tuo artikkeli on elokuulta 1979, jolloin Burns oli juuri lopettelemassa Fedissä.

Burns piti reaalikorkoja alhaalla. Mielestäni on huikeaa miten totaalisesti päinvastainen narratiivi voi olla. Nykyään kaikki ajattelevat että negatiiviset reaalikorot omalta osaltaan tukee osakemarkkinoita. 1979 tilanteessa tuota oli kokeiltu mutta narratiivi oli täysin eri.

Boldasin tuosta kohdan jossa viitataan negatiivisten reaalikorkojen vaikutukseen. Edistää kulutusjuhlaa ja spekulointia mutta pörssi nyt vaan ei ole se missä action on.

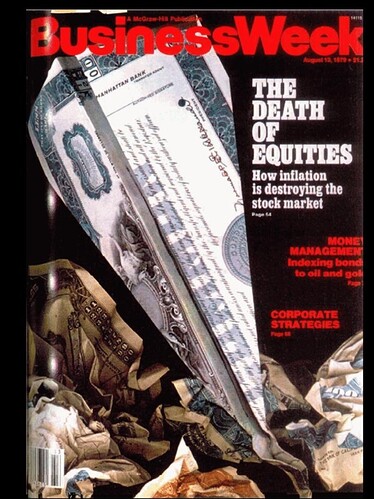

How inflation is destroying the stock market

At least 7 million shareholders have defected from the stock market since 1970, leaving equities more than ever the province of giant institutional investors. And now the institutions have been given the go-ahead to shift more of their money from stocks—and bonds—into other investments. If the institutions, who control the bulk of the nation’s wealth, now withdraw billions from both the stock and bond markets, the implications for the U.S. economy could not be worse. Says Robert S. Salomon Jr., a general partner in Salomon Bros.: “We are running the risk of immobilizing a substantial portion of the world’s wealth in someone’s stamp collection.”

Few corporations can find buyers for their stocks, forcing them to add debt to a point where balance sheets seem permanently out of whack.

Until now, the flight of institutional money from the financial markets has been merely a trickle. But if could turn into a torrent if this year’s 60% increase in oil prices touches off a deep recession while pushing inflation sky-high.

Further, this “death of equity” can no longer be seen as something a stock market rally—however strong—will check. It has persisted for more than 10 years through market rallies, business cycles, recession, recoveries, and booms. The public was first drawn to equities in big numbers in the 1950s by a massive promotion campaign by Wall Street that worked because the economic climate was right: fairly steady growth with little inflation.

Younger investors, in particular, are avoiding stocks. Between 1970 and 1975, the number of investors declined in every age group but one: individuals 65 and older. While the number of investors under 65 dropped by about 25%, the number of investors over 65 jumped by more than 30%. Only the elderly who have not understood the changes in the nation’s financial markets, or who are unable to adjust to them, are sticking with stocks.

Even if the economic climate could be made right again for equity investment, it would take another massive promotional campaign to bring people back into the market.

For better or for worse, then, the U.S. economy probably has to regard the death of equities as near-permanent condition—reversible some day, but not soon.

Says Alan B. Coleman, dean of Southern Methodist University’s business school: “We have entered a new financial age. The old rules no longer apply.”

The one rule whose demise did the stock market in could be summed up thus: By buying stocks, investors could beat inflation. Stocks were a reasonable hedge when inflation was low. But they proved helpless against the awesome inflation of the past decade. “People no longer think of stocks as an inflation hedge, and based on experience, that’s a reasonable conclusion for them to have reached,” says Richard Cohn, an associate professor of finance at the University of Illinois.

Just last May, for example, First-Citizens Bank & Trust Co., in Greenville, S.C., began accepting diamonds in its self-directed trust accounts because of incresing demand from its customers. “At least 95% of these customers are trying to escape what inflation is doing to stocks,” declares Vice-President Ronald O. Holland.

"Given the type of consistent high-level inflation we’ve been

experiencing, the stock market represents speculation, and some tangible assets represent the opposite,” says Edward R. McMillan, chief economist for Seattle’s Rainier National Bank.

The average stock price is now about 60% of the replacement value of the underlying assets. Thus, a company can acquire $1 worth of assets by paying about 60~ for its shares.

Private pension funds, for example, which control some $300 billion in assets and are the single most important factor in the financial markets, put more than 120% of their new cash into equities in the late 1960s. To do so, they even sold bonds to raise money to buy stocks. Today the amount of new pension money flowing into equities is a minuscule 13% as the funds have built up their cash portions or stuffed their portfolios with short-term securities paying high rates.

Undeniably, the U.S. is in the midst of a fundamental shift—aided by government monetary and fiscal policies—away from investment in favor of immediate consumption. “Savers are subsidizing borrowers, and debt has become more attractive than capital formation,”

The exploding markets are feeding a speculative fever that is very close to out-and-out gambling. Indeed, speculators in commodities lose on most trades and must rely on an occasional big win to put them ahead—something that no longer deters even conservative institutional investors. Gaasedelen of the Minneapolis Teachers Retirement Fund Assn., for example, intends to put some assets into “speculative ventures,” where the returns are huge enough 20% of the time to offset the losses that occur the rest of the time.

Today, the old attitude of buying solid stocks as a cornerstone for one’s life savings and retirement has simply disappeared. Says a young U.S. executive: “Have you been to an American stockholders’ meeting lately? They’re all old fogies. The stock market is just not where the action’s at.”