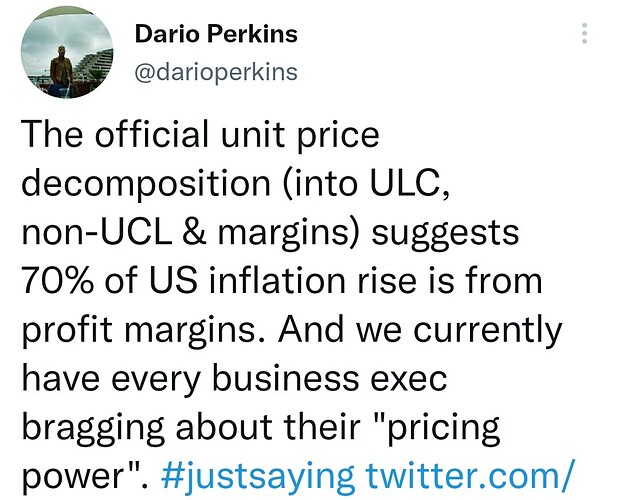

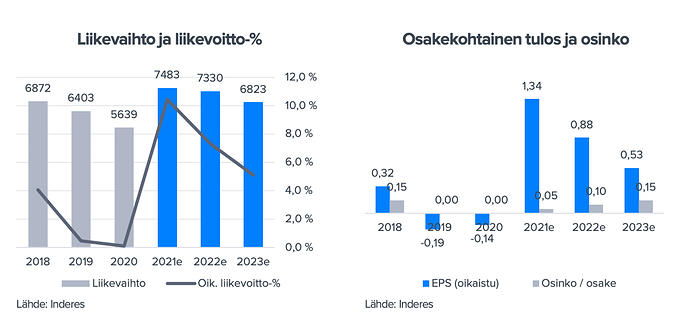

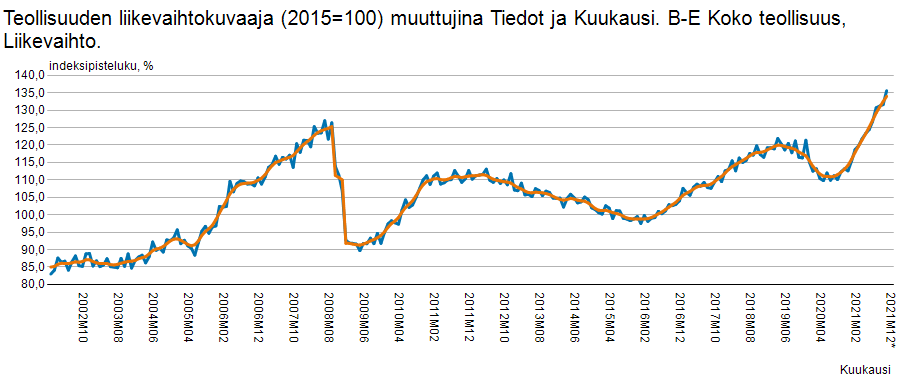

Kovan suhdannenousun vaikutuksia yrityksiin ja sijoittajien tunnelmiin ja yleiseen ilmapiiriin voisi ehkä eritellä näin:

- ensinnäkin yritetään hahmottaa vaikutukset niin että yritetään puhdistaa hintojen nousun vaikutusta mahdollisimman tarkasti pois

- toiseksi tutkitaan se elementti että ihan vaan hintojen nousu saa monen yhtiöihin ja pörssiin liittyvän ilmiön näyttämään erilaiselta kuin se muuten näyttäisi

-

Joskus voi olla niin että suhdannenousun reaalisten vaikutusten lisäksi myös hintojen nousuun liittyvät kangastukset otetaan täysillä mukaan yhä optimistisimmiksi käyviin narratiiveihin.

-

Joskus voidaan olla ihan toisessa ääripäässä: kukaan ei oikein kunnolla osaa innostua niistä oikeista suhdannenousun hyvistä reaalisista vaikutuksista. Nimittäin huomio on fiksoitunut kiihtyvään inflaatioon ja kaikkeen ikävään mitä siitä saattaa seurata.

Voidaan vertailla vaikkapa sijoittajien tunnelmia USA:ssa vuonna 1968 ja 1984. Näistä 1968 on erinomainen esimerkki tilanteesta 1 ja kesä 1984 tilanteesta 2. Inflaatiovauhti oli molempina hetkinä täysin sama, 4 % pintaan.

Vuonna 1968 sijoittajilla ei ollut tuoreita inflaatioon liittyviä traumoja mutta 1984 todellakin oli. Yhteistä oli noille hyvä suhdannetilanne, mutta osake- ja bondimarkkinoiden sentimentti ja arvostustasot olivat aivan erilaiset.

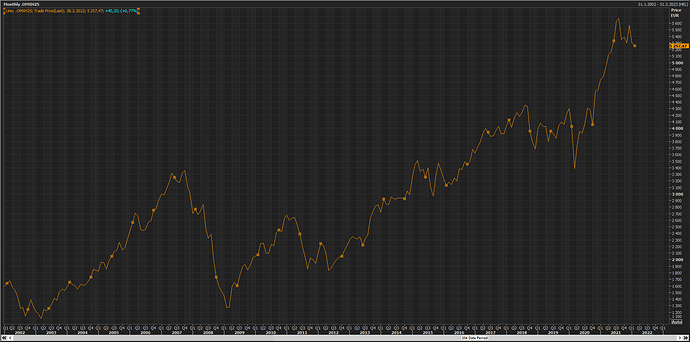

Viime vuonna kovan suhdannenousun reaaliset vaikutukset ja hintojen nousun aiheuttamat näköharhat pääsivät molemmat täysillä mukaan yhä optimistisimmiksi käyviin narratiiveihin. Tämä ei ole ihme sillä sijoittajien inflaatiokokemukset olivat vielä paljon kauempana kuin tuossa vuoden 1968 esimerkissä olivat.

Alla on mielenkiintoinen kuvaus ajalta jolloin Fediä ei vielä ollut olemassa. Hinnat ja korot olivat kapitalististen markkinavoimien sanelemat. Ei ollut julkista instanssia jolla olisi ollut oma linjansa ja työkalunsa vaikuttaa hintojen kehitykseen tai korkoihin. Kultakannan takia oletusarvo oli että hinnat välillä nousevat ja välillä laskevat mutta pitkällä aikavälillä hinnoilla ei ole mitään trendiä ylös- tai alaspäin. Tämä tosiasia ei silti estänyt juuri ketään tempautumasta mukaan suurelta osin hintojen nousun luomaan noususuhdannehuumaan.

Jos vertaa tilannetta 2021 johonkin 110 tai 120 vuotta aiemmin olleeseen huumaan, ihmisen henkiset resurssit ja rajoitteet eivät ole muuttuneet.

Asetelmassa jotain samaa: 1900-luvun alussa ei ollut julkista instanssia jolle inflaatio olisi kuulunut. Vuonna 2021 oli julkiset instanssit joiden toimialaan hintavakaus periaatteessa kuului mutta jotka sanoivat “inflaatio menee ihan kohta ohi aivan itsekseen; nauttikaa täysillä nousumarkkinanarratiivienne jokaisesta aromista”.

A psychological influence of a much wider scope also operates to help a bull market along to unreasonable heights. Such a market is usually accompanied by rising prices in all lines of business and these rising prices always create, in the minds of business men, the impression that their various enterprises are more profitable than is really the case.

One reason for this false impression is found in stocks of goods on hand. Take the wholesale grocer, for example, carrying a stock of goods which inventories $10,000 in January, 1909. On that date Bradstreet’s index of commodity prices stood at 8.26. In January, 1910, Bradstreet’s index was 9.23. If the prices of the various articles included in this stock of groceries increased in the same ratio as Bradstreet’s list, and if the grocer had on hand exactly the same things, he would inventory them at about $11,168 in January, 1910.

He made an additional profit of $1,168 during the year without any effort, and probably without any calculation, on his part. But this profit was only apparent, not real; for he could not buy any more with the $11,168 in January, 1910, than he could have bought with the $10,000 in January, 1909. He is deceived into supposing himself richer than he really is, and this false idea leads to a gradual growth of extravagance and speculation in every line of business and every walk of life.

The secondary results of this delusion of increased wealth because of rising prices, are even more important than the primary results. Our grocer, for example, decides to spend this $1,168 for an automobile. This helps the automobile business. Hundreds of similar orders induce the automobile company to enlarge its plant. This means extensive purchases of material and employment of labor. The increased demand resulting from a similar condition of things in all departments of industry produces, if other conditions are favorable, a still further rise in prices; hence at the end of another year the grocer perhaps has another imaginary profit, which he spends in enlarging his residence or buying new furniture, etc.

The stock market feels the reflection of all this increased business and higher prices. Yet the whole thing is psychological, and sooner or later our grocer must earn and save, by hard work, economical living and shrewd calculation, the amount he has paid for his automobile or furniture. Again, rising stock prices and rising commodity prices react on each other. If the grocer, in addition to his imaginary profit of $1,168 sees a ten per cent, advance in the prices of various securities which he holds for investment, he is encouraged to still larger expenditures; and likewise if the capitalist notes a ten per cent advance in the stock market, he perhaps employs additional servants and enlarges his household expenditures so that he buys more groceries.

Thus the feeling of confidence and enthusiasm spreads wider and wider like ripples from a stone dropped into a pond. And all of these developments are faithfully reflected by the stock market barometer. The result is that, in a year like 1902 or 1906, the high prices for stocks and the feverish activity of general trade are based, to an entirely unsuspected extent, on a sort of pyramid of mistaken impressions, most of which may be traced, directly or indirectly, to the fact that we measure everything in money […]